Introduction¶

A simple concurrent program¶

Writing correct concurrent programs is far more difficult than writing correct sequential programs. Let us start with a very simple program that repeatedly prints “Hello, ” and “world!” in alternating order. We split this program into three different processes: two producers that output strings “Hello, ” and “world!”, respectively, and a consumer that alternately prints the strings that it obtains from these producers, starting of course with “Hello, ”.

If you are asked to write a small program that implements the above informal specification, you may come up with the following Java code:

import java.util.concurrent.Semaphore;

public class Main {

private static final Semaphore greenSemaphore = new Semaphore(0);

private static final Semaphore redSemaphore = new Semaphore(1);

private static final Semaphore bufferSemaphore = new Semaphore(1);

private static String buffer = null;

public static void main(String[] args) {

Thread redProducer = new Thread("Red Producer") {

public void run() {

while (true) {

for (int i = 0; i < 30000000; ++i);

String redText = "Hello, ";

try {

redSemaphore.acquire();

bufferSemaphore.acquire();

buffer = redText;

bufferSemaphore.release();

greenSemaphore.release();

} catch (InterruptedException e) { }

}

}

};

Thread greenProducer = new Thread("Green Producer") {

public void run() {

while (true) {

for (int i = 0; i < 50000000; ++i);

String redText = "world! ";

try {

greenSemaphore.acquire();

bufferSemaphore.acquire();

buffer = redText;

bufferSemaphore.release();

redSemaphore.release();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

};

Thread blueConsumer = new Thread("Blue Consumer") {

public void run() {

int k = 0;

while (k < 10) {

for (int i = 0; i < 40000000; ++i);

try {

bufferSemaphore.acquire();

if (buffer != null) {

System.out.print(buffer);

buffer = null;

k++;

}

bufferSemaphore.release();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

};

redProducer.start();

greenProducer.start();

blueConsumer.start();

try {

blueConsumer.join();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

The main method in the above Java code instantiates three different Java threads, namely a Red and a Green producer and a Blue consumer. These threads communicate with each other via a shared buffer that is protected by a semaphore. If a thread wants to operate on the buffer, it tries acquire the semaphore that protects the buffer. Once acquired, the process can write to the buffer without being disturbed by any other process. Finally, the process releases the semaphore, which allows other processes to acquire it and operate on the buffer undisturbed.

This program uses additional turn-keeping semaphores to alternate the writes by producers to the buffer: each producer has its own turn-keeping semaphore. If a producer wants to write to the buffer, it first tries to acquire its turn-keeping semaphore. After writing to the buffer, the producer hands over the turn to write to the other producer, by releasing the latter’s turn-keeping semaphore.

Analysis¶

Let us now analyze this Java implementation by answering a few simple questions.

- Where is the “Hello, ” string computed?

On line 15: String redText = “Hello, “;.

- Where is the text printed?

On line 53: System.out.print(buffer);.

For the next question, however, it is not possible to point at a single line (or even a contiguous segment) of code:

Where is the protocol?

- What determines which producer goes first?

This is determined by the initial values of the semaphores on lines 5 and 6, together with the acquire statements of semaphores on lines 17, and 33.

- What determines that the two producers alternate?

This is determined by the initial values of the semaphores on lines 5 and 6, together with the acquire and release statements of the semaphores on lines 17, 21, 33, and 37. Observe that 4 out of these 6 lines are the same lines involved in the answer to question 3.a; a fact that means if we change one of these common lines of code with the intention of modifying one aspect of the protocol, we must simultaneously consider whether and how this change affects the other aspect of the protocol.

- What takes care of buffer protection?

This is established by the acquire and release statements of the buffer semaphore on lines 18, 20, 34, 36, 51, and 57.

The reason why Question 3 is much more difficult and has a more complicated answer is that unlike the computation in this application, its protocol is implicit. Modern programming languages provide suitable constructs to explicitly specify computation as concrete, contiguous segments of code; however, the constructs that they provide to program concurrent software allows programmers to specify concurrency protocols only indirectly, as the side-effect of the execution of (concurrency) primitive actions scattered throughout the code of various processes.

For such a simple program, you may argue that the fact that the protocol is implicit is not big deal. However, if you really think this, then you may be surprised by the output when you run the above application:

Hello, world! Hello, Hello, world! Hello, Hello, Hello, Hello, Hello,

If you expected to see nothing but “Hello, world!” as output, then you must agree that there is a bug! Can you spot the error?

Reo protocols¶

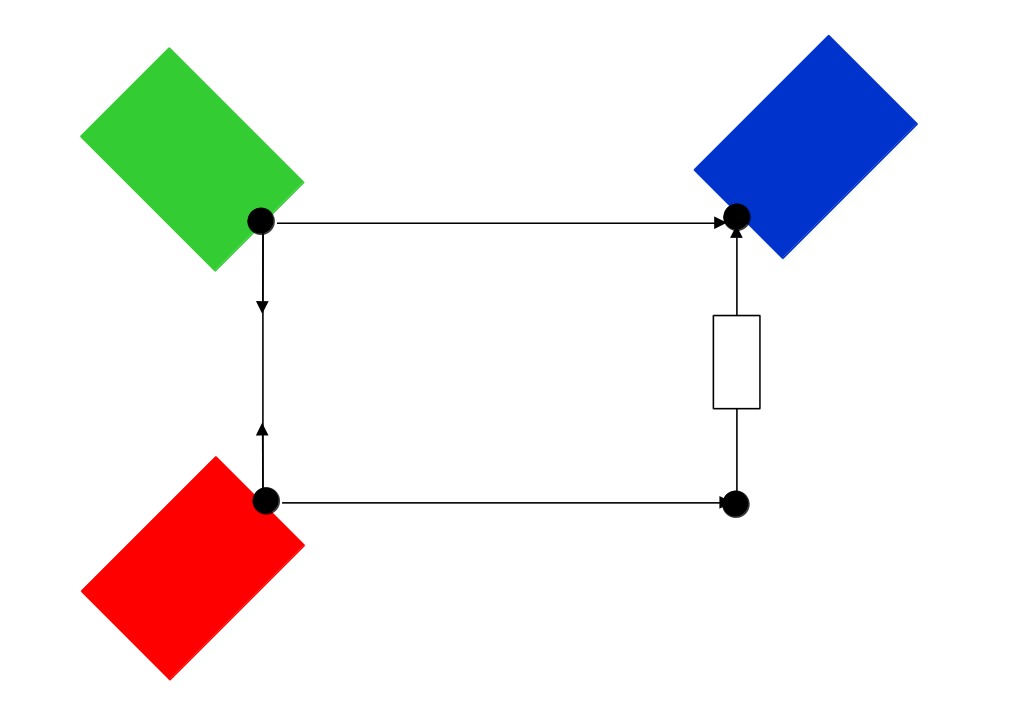

The Reo language offers a solution by providing a domain specific language that allow you to specify your protocol explicitly, as a concrete, identifiable piece of software. The following diagram shows an example of such an explicit protocol:

Every process is represented as a box together with a set of ports that define the interface of each process. These boxes, called components, are connected via a network of channels and nodes, which constitutes the protocol. The components now interact with each other by offering values to the protocol. The protocol, then, coordinates the exchanges of values amongst components.

The channel between Red and Green is a syncdrain channel that repeatedly accepts a data item from each of its input ends in a single atomic action, and loses both data items. The channel between Red and Blue is a sync channel that atomically takes a data item from its input end and passes this data item through its output end. The other incoming channel connected to Blue is a fifo1 channel that has a buffer (depicted as the box in the middle of the arrow) with the capacity to store a single data item. The buffer of this channel is initially empty. Whenever its buffer is empty, this channel can accept a single data item through its input end, which it then places in its buffer, making it full. With its buffer full, this channel cannot accept input. When its buffer is full, this channel allows a get operation on its output end to succeed by offering it the data item in its buffer, after which its buffer becomes empty. As long as its buffer is empty, a get operation at its output end remains pending, because the channel has no data to offer.

Suppose Red wants to output some data. Then, Red issues a put request at its port. As soon as Green has also issued a put request, and Blue has issued a get request, the protocol synchronously (i.e., atomically) accepts the data produced by Red and Green, offers Green’s data to Blue, and stores Red’s data in the buffer of the fifo1 channel. As long as this buffer remains full, the fifo1 channel cannot accept any more data, which means further put requests by the producers will suspend until this buffer becomes empty. Upon the next get request by Blue, Blue receives the data from the buffer, which empties the buffer and returns the protocol to its initial configuration. Therefore, this protocol implements the informal specification that prescribes alternation.

Although we may think of such a protocol as message passing, the code that is generated by the compiler is (depending on the target) based on shared memory.

Compilation¶

The first step consist of isolating the computation that is done in each process.

To this end, we create a Java class in Processes.java that contains the a method for each original process:

import nl.cwi.reo.runtime.Input;

import nl.cwi.reo.runtime.Output;

public class Processes {

public static void Red(Output<String> port) {

while (true) {

for (int i = 0; i < 30000000; ++i);

String datum = "Hello, ";

port.put(datum);

}

}

public static void Green(Output<String> port) {

while (true) {

for (int i = 0; i < 50000000; ++i);

String datum = "world! ";

port.put(datum);

}

}

public static void Blue(Input<String> port) {

for (int k = 0; k < 10; ++k) {

for (int i = 0; i < 40000000; ++i);

String datum = port.get();

System.out.print(datum);

}

}

System.exit(0);

}

Note that the code of each Java method is completely independent of any other method, since no variables are explicitly shared. Synchronization and data transfer is delegated to put and get calls on output ports and input ports, respectively. This way, we strictly separate computation from interaction, defined by the protocol.

In the next step, we declare the protocol by means of the Reo file called main.treo:

import reo.syncdrain;

import reo.sync;

import reo.fifo1;

// The main component

main() { green(a) red(b) blue(c) alternator(a,b,c) }

// The atomic components

red(a!String) { #JAVA "Processes.Red" }

green(a!String) { #JAVA "Processes.Green" }

blue(a?String) { #JAVA "Processes.Blue" }

// The alternator protocol

alternator(a,b,c) { syncdrain(a, b) sync(b, x) fifo1(x, c) sync(a, c) }

This Reo file defines the main component, which is a set containing one instance of each of Red, Green, and Blue processes, and an instance of the alternator protocol.

The definitions of Red, Green, and Blue processes just refers to the Java source code from Processes.java.

The definition of the alternator protocol is expressed using primitive Reo channels, which are imported from the standard library.

Before we can compile this Reo file into Java code, please first follow the instructions in Installation to install the Reo compiler.

Next, change directory to where main.treo and Processes.java are located, and execute:

reo main.treo javac Main.java java Main

These commands respectively

- compile Reo code to Java source code (by generating

main.java),- compile the generated Java source code to executable Java classes, and

- execute the complete program.

Since the alternator protocol defined in main.treo matches the informal specification, and since the generated code correctly implements the alternator procotol, the output now looks as follows:

Hello, world! Hello, world! Hello, world! Hello, world! Hello, world!